No Free Lunch and Northern Lights

24 May 2022

Lars Gebraad, a PhD student in the Seismology and Wave Physics group at ETH Zürich, reports on his HPC-Europa3 research visit to the School of GeoSciences at the University of Edinburgh.

I’m an imaging guy. Both professionally, for my career, and casually, in my free time. As a PhD student in Bayesian Full-Waveform Inversion, I concern myself with making images of the interior of the Earth, while ascribing it with quantified measures of uncertainty. Catch me on a random clear night, however, and I might be doing some astrophotography.

When Andrew Curtis (Chair of Mathematical Geoscience, University of Edinburgh), my host-to-be, approached me at a mini seismology conference in the Bavarian Alps, we only had the former in mind. Around that time, his group had just published their first probabilistic image of a synthetic Earth using variational methods. This was completely perpendicular to the method I had used (Markov chain Monte Carlo) to publish almost exactly the same result. In fact, we had communicated a-priori to see if our distinctive methods would produce the same posterior belief if applied to the same problem. They did. This was March 2020.

At the conference, Andrew told me about the HPC-Europa3 programme, and how it would allow us to research the differences in Bayesian appraisal methods for seismological imaging, while giving us a very practical collaboration framework. I would be able to visit, he and researchers in his group would be able to directly collaborate on code with me, and we would get some HPC allocation. We set out to write an application, and it passed! A slight hiccup: the world was closing down due to some nasty virus. We indefinitely postponed our original Autumn 2020 visit.

Seismic imaging

Luckily, some of the world’s brightest got working and made some very much needed vaccines. As Andrew and I kept the infection numbers, government mandates and our own common sense in mind, it turned out that Autumn 2021 did seem like a workable period to visit the UK. Taking the train through Germany, The Netherlands, Belgium, a tiny bit of France, and England I arrived at long last in Edinburgh. A doctoral student of Andrew’s (who is an old classmate of mine) was waiting for me at Waverley. Quite a ‘homecoming’ to see a familiar face in a strange place.

One of the big questions that surrounds seismic imaging is which algorithm should be used to produce the most qualitative image as efficiently as possible. By virtue of the no free lunch theorem, every algorithm performs equally well, averaged over all problems. That raises the question however, what if we limit the problems to seismological ones?

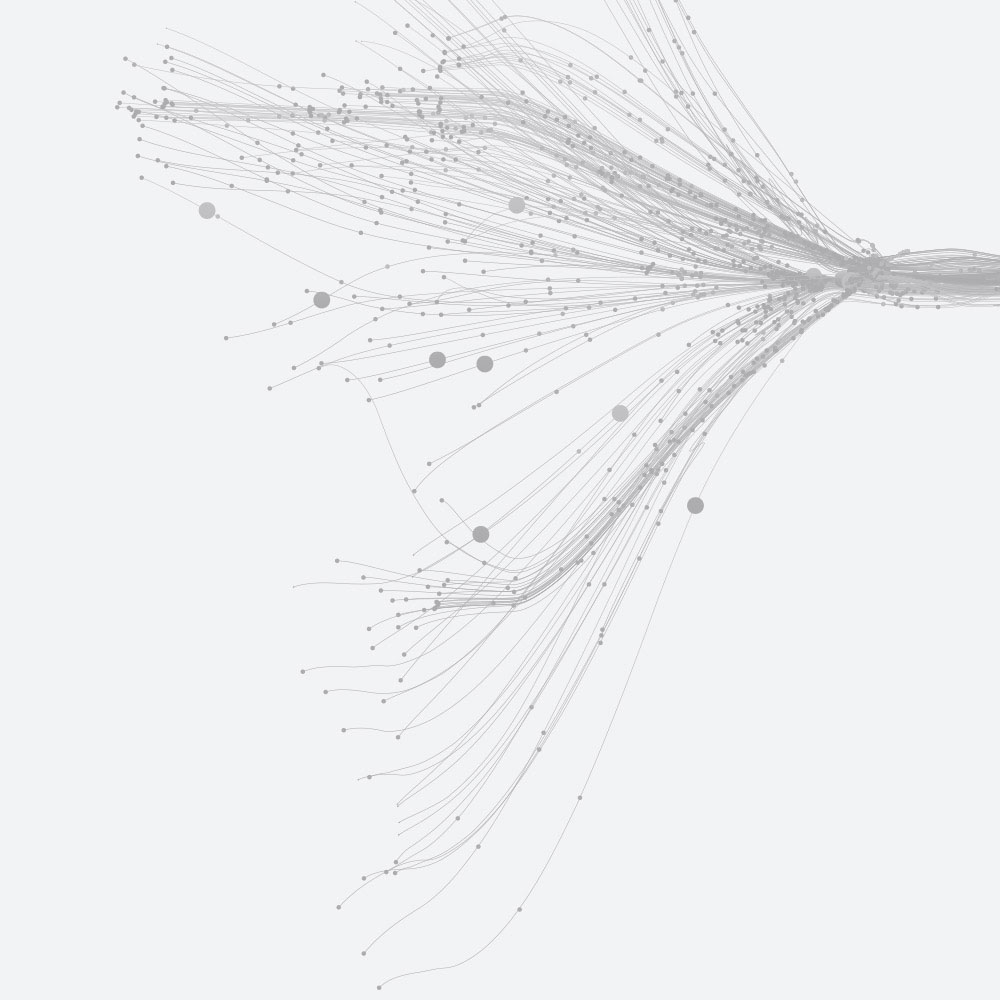

Over the visit, Andrew, Xin Zhang (a PostDoc in the group) and I tested various measures to score algorithms when applied to Bayesian imaging problems. After a few iterations we settled on entropy. Similar to its thermodynamical namesake, statistical entropy concerns itself with the disorder of something. Entropy in our context refers to the amount of information present.

To test if an algorithm performs well for seismological imaging, we decided to test if it preserves the total amount of entropy. We let the algorithm appraise a posterior generated from recorded data and prior beliefs. Subsequently we test if the algorithm produces an image with as much entropy as the prior belief and data combined. If the entropy (or, information) is preserved to a high degree, the algorithm performs well. By averaging this over many possible images and many evaluations, we can get absolute numbers on the ‘quality’ of an algorithm. As we suspected, the algorithms we both use strongly outperform classical ones such as random walks.

Averaging many runs of an algorithm obviously becomes quite expensive after a while. As we need to run MCMC sampling and variational methods in high dimensional spaces, we haven’t progressed beyond 8 dimensions as of the end of the physical HPC-Europa3 visit. Although supercomputers come a long way in helping us with this kind of scaling, the Curse of Dimensionality means we will likely never be able to answer this question for arbitrarily high dimensions. For now, a part of our compute budget remains, and we will increase complexity.

Astro imaging

Somehow I found myself halfway during my PhD buying a fancy camera. At first just for landscape photography. At some point, my work managed to sneak in. Now I find myself spending early Sunday mornings, 1 to 4 am, sitting by a motorised tripod imaging the stars. When I get home? Straight to processing the data. Sleep’ll come later.

Jesting aside, knowing that I’d go to Scotland got me very excited, also beyond the science. I love the outdoors, impressive landscapes and dark skies, so it really felt like the perfect place to spend a few months. Although the city itself is not as close to impressive mountains as my science-hometown of Zurich, the Pentlands and Arthurs Seat offer quite a few days of outdoor exploration.

Truth is, I did spend 8 or so of the 12 weekends north of Edinburgh. At the affordable Aygo rental company they knew me by name after half my visit, asking where my weekend trip was going this time. I made it a point to see as many places as possible. Loch Lomond, Ben Arthur, Balmoral Castle, The Three Sisters at Glen Coe and Dalwhinnie are all great day-tours from Edinburgh itself. I finished up my visit by a week of travel based from Inverness, seeing places like Torridon, Stac Pollaidh, the Isle of Skye and Glen Etive. I won’t try to do them justice with words, the pictures must suffice.

The highlight of the short three months might have been already around November, the very middle of my stay. At lunch at the department on a random Friday I heard about a rather strong solar flare heading our general direction. Clear weather and an enthusiastic colleague made me impulse-rent another Aygo, and off we set on Saturday afternoon to find a high spot in the Cairngorms. Parking on the slopes of Cairn Gorm itself, we waited for nightfall and the appearance of dancing lights. After 2 hours of waiting, we were left demotivated and cold (without car heating). Driving past a few other stargazing spots (the shores of Loch Morlich and Loch an Eilein) we finally settled for one last attempt at the dedicated dark site of Tomintoul.

For what first looked like industrial light pollution, those lights in the sky sure did move fast! Lo and behold, after a few minutes of adjusting our eyes to the dark, we were treated to the colourful spectacle of the Aurora. When our initial excitement wore off (took more than an hour though!) we got some sleep in the car with the lights still dancing around us. A magical treat.

Glen Etive lit up by the last light of the day. Skyfall was filmed on the road through this Glen.