UKRI-funded Metascience Fellow to rethink AI and wicked problems

18 February 2026

In January Batool Almarzouq joined EPCC and the Software Sustainability Institute as a UKRI-funded AI Metascience Fellow. As she explains here, her work will explore how AI is shaping disruptive science and influencing scientific norms in research into complex, "wicked" problems.

My journey inside the research machine

My career has moved across disciplines, institutions, and roles, shaped by a drive to challenge existing structures, explore new spaces, and build more inclusive, collaborative, and transparent research cultures.

I completed my PhD at the intersection of Pharmacology and Computational Biology at the University of Liverpool, where I focused on breast cancer. My research combined machine learning with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations on high-performance computing (HPC) systems. I began my research journey in traditional academic settings as a postdoctoral researcher, splitting my time between coding and wet-lab work. I spent countless hours at the bench, running cell cultures, breaking down complex problems into small biological questions, and investigating the pharmacology of cancer mutations.

Over time I grew curious about what happens after the paper leaves the lab. I wanted to understand how the ‘research machine’ works behind the scenes, so I moved into infrastructure roles. Here I became attuned to the hidden architecture of science: how funding flows, how priorities are set, and how communities are often unintentionally excluded from shaping the research that is meant to benefit them.

I worked as Research Project Manager for the AI for Multiple Long-Term Conditions: Research Support Facility (AIM RSF) at The Alan Turing Institute. The AIM RSF was part of a £23 million National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) programme focused on artificial intelligence and multi-morbidity. Later, before joining EPCC, I served as Data Service Manager for the Imagery Smart Data Service (Imago), part of the Smart Data Research UK (SDR-UK) programme funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC). This programme is focused on improving the usability of satellite imagery for public health, urban planning, and policy.

Alongside these roles, I have worked closely with grassroots communities, advocating for open science, championing pluralism in how we create knowledge, and designing inclusive spaces. I have thought deeply about how communities are systematically excluded from research agendas and how we might navigate the contradictory systems we live in.

These experiences have given me a dual perspective on what it means to be a scientist, a researcher, and an intellectual in a polycrisis world. As we look deeper into our discipline, we must also look up. Up at the container, the system, the institution. Where we publish, the way we speak to ourselves is in a language no one else understands. How do we amplify our agency inside an academic system built in the 19th Century for 21st Century problems? These are the questions that move me. They pulled me from the narrow focus of my discipline, the place where I once worked in isolation, toward the system itself.

The AI Metascience Fellowship, funded by the UKRI Metascience Unit, is a space to follow them. The Unit was established in late 2023 as part of the Government's response to the Nurse Landscape Review. It was created to gather and amplify the work already being done by researchers across the world who are turning the lens of science back on itself. This is an international fellowship, a cohort of researchers spread across the UK, Canada, and the United States. We ask different questions and come from different disciplines, different traditions. But we are all circling the same unsettled ground: how does AI reshape the norms, the practices, the very fabric of how knowledge gets made? My own project sits at the intersection of all this, asking how AI is reshaping scientific norms, collaboration dynamics, and disruptive science in research on complex, wicked problems. (Read more about the Fellowship on the UKRI website.) If you have never come across Metascience before, I have recently written a provocative article on Medium untangling what the term means: Metascience for whom? A question as old as science.

Wicked problems, narrow tools

What exactly do we mean by a ‘wicked problem’?

First introduced by design theorists Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber in 1973, wicked problems are intricate challenges characterised by incomplete, contradictory, and evolving requirements. Consensus is inherently difficult because every attempt to solve a wicked problem changes the problem itself.

UKRI and the United Nations refer to these as ‘global challenges’. Climate change, public health crises, immigration, and biodiversity loss all fall into this category. Each requires transdisciplinary collaboration, systems thinking, and the meaningful integration of societal actors [1].

Crucially, wicked problems exist in complex systems, not merely complicated ones. A complicated system, like a jet engine or a Swiss watch, can be broken down into deterministic parts. Once you understand each component, you can predict and control the whole. Complex systems, however, exhibit non-linear behaviours. Every intervention alters the surrounding context and creates new, often unforeseen, effects. The strategies and tools that work for complicated problems are largely not interchangeable with those required for wicked ones.

Artificial intelligence is increasingly embedded in research ecosystems and is thought to be a powerful tool for tackling these issues [2]. Yet its integration raises urgent questions. How do algorithmic systems reshape scientific norms, collaboration dynamics, and funding structures when applied to wicked problems? There is a growing concern that AI might inadvertently reinforce incremental refinements, optimising for what is measurable rather than what is necessary, rather than supporting the disruptive thinking these challenges demand.

Disruptive science

Disruptive science refers to research that fundamentally shifts paradigms and drives transformative change, rather than delivering incremental improvements [3]. It does not just add to the stack of knowledge; it reorders it.

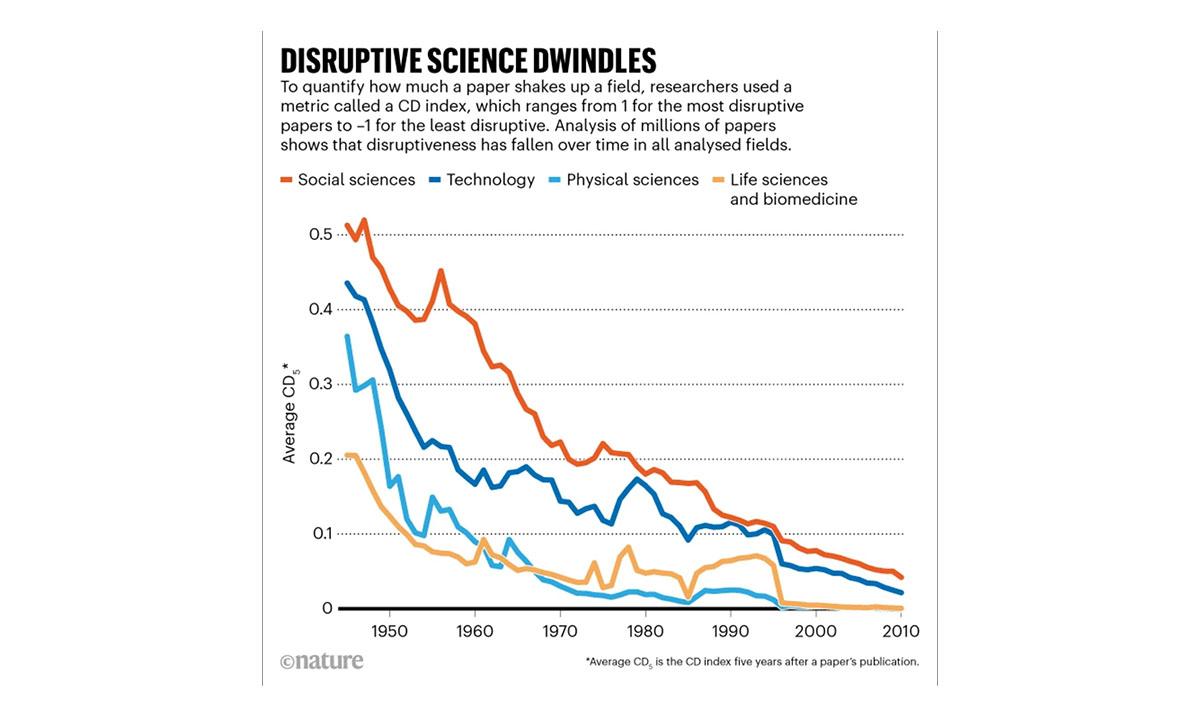

Recent analyses of 45 million scientific papers and 3.9 million patents reveal a striking trend: a 91–100% decline in disruptive contributions since the mid-20th century, as measured by metrics like the Consolidation-Disruption (CD) index [3]. While this finding is debated—some argue it reflects a shift toward rigorous validation rather than stagnation—it signals systematic changes in research practices. Teams have grown larger, foci have narrowed, and the pressure to publish frequently has incentivised ‘safe’ science [3-5].

Figure 2: The number of research papers published has skyrocketed over the past few decades, but the ‘disruptiveness’ of those papers has dropped. Source: Park, M., Leahey, E. & Funk, R. J. Nature 613, 138–144 (2023).

AI risks exacerbating this trend, often indirectly. Machine learning models trained on historical datasets learn to prize what has already been funded and published. They optimise for ‘safe bets’. Without deliberate intervention, AI tools may steer researchers toward incrementalism and away from the high-risk, high-reward paths that generate paradigm shifts [6].

How will we study the system

This fellowship asks how AI is reshaping knowledge production inside transdisciplinary research on wicked problems. Not just how it changes scientific practices, but how it shifts funding priorities, redraws disciplinary boundaries, and remakes research culture from the inside out. It asks us to rethink how funding systems might better support epistemic diversity, intellectual risk-taking, and systems thinking. The work focuses on two interconnected themes: epistemic shifts, which is another way of asking how we know what we know, and disruptive thinking, which is about how we break from established patterns.

To do this, I will combine ethnographic studies of Grand Challenge research programmes with extensive mapping of the funding landscape. I will analyse the skill competencies that are being lost, things like experimental design and contextual interpretation, and those that are emerging, particularly roles that bridge technical and societal domains. The study will also ask whether our growing reliance on automated tools is eroding foundational research skills. Are we trading the ability to ask bold questions for the capacity to process large datasets? What new roles are emerging at the interface of AI and society, and how can funding schemes better support them?

These findings will form the basis of a set of actionable recommendations for funders. To ensure they land where they matter, I will design two interactive events that bring together policymakers, researchers, and community stakeholders.

Misaligned funding for AI-driven research does not merely waste resources. It risks compounding intellectual conformity at exactly the moment we need cognitive diversity most, in a polycrisis world. In the face of climate breakdown, pandemics, and widening inequality, deploying AI as yet another tool that reinforces existing silos is not a neutral choice. It is a failure of imagination.

This work calls for a radical reconceptualisation of how funding structures shape AI's role in science. We have an opportunity to move AI from being an algorithmic enforcer of disciplinary boundaries to becoming a genuine catalyst for convergence across knowledge systems. The future of research, and our ability to address the wicked problems that define our era, depends on it.

References

- Rittel & Webber (1973). Wicked Problems. Policy Sciences.

- Royal Society. Science in the Age of AI. Royal Society; 2019. Available at: https://royalsociety.org/news-resources/projects/science-in-the-age-of-ai

- Park M., Leahey E., Funk R.J. Papers and patents are becoming less disruptive over time. Nature. 2023;613(7942):138–144.

- Funk RJ et al.; Declining Disruptive Science – Can It Be Reversed? Children's Innovation Centre; 2023; Available at Nature DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05543-x

- Researcher.Life Blog; Disruptive Science Plummets Over Past 50 Years; 2023; Available at Nature DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05543-x

- Kaiser M, Gluckman P. Looking at the Future of Transdisciplinary Research. International Science Council; 2023. Available at: https://council.science/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/2023-04-26Futureoftransdisciplinaryresearch.pdf

- Royal Society Open Science Editors. Making the Most of AI’s Potential: Cross-disciplinary Perspectives on the Role of AI in Science and Society. Royal Society Open Science; 2024. Available at: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsos.241306

- Rittel HWJ., Webber MM. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci. 1973;4(2):155–169.

- A User-Focused Transdisciplinary Research Agenda for AI-Enabled Health Tech Governance; SSRN; 2019 Jan 1; Available at SSRN: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3385398